Visionary genius and its derivatives: from the twentieth century to the near future

The twentieth century was the century in which genius ceased to be merely an individual talent and transformed into a collective force capable of anticipating, with the perspicacity of those who can read the hidden signs of the present, the forms of a future that did not yet exist but was already pressing on the threshold of consciousness. It was no longer a matter of imagining impossible worlds, but rather of perceiving, with an almost prophetic intuition, the lines of development that would radically change daily life, the perception of time, and the structure of society. Thus, Einstein, with relativity, dissolved Euclidean and Newtonian certainties, opening a path to an elastic, mobile, and fluid universe; Turing glimpsed the possibility of machines thinking, and in doing so inaugurated the era of artificial intelligence; McLuhan spoke of a global village when the word "net" still evoked only images of fishermen; And Joe Colombo, with his visionary imagination, envisioned phones in pockets, working from home, and minds augmented by electronic brains, at a time when all this seemed pure science fiction. Our journey begins here.

Insight as the architecture of the future

The visionary genius, therefore, has never been merely someone who invents or creates, but someone who deciphers the present like a secret code, reading within the folds of reality what is not yet manifest. It is a philosophical rather than a technical act: the ability to grasp the essence of becoming, to intuit that the shape of the world is not given once and for all, but is a process of constant metamorphosis. In this sense, visionary genius is the true legacy of the twentieth century, because it taught us that the future is not a destiny to be awaited, but a project to be designed, and that perspicacity is the only compass capable of orienting humanity in a sea of possibilities.

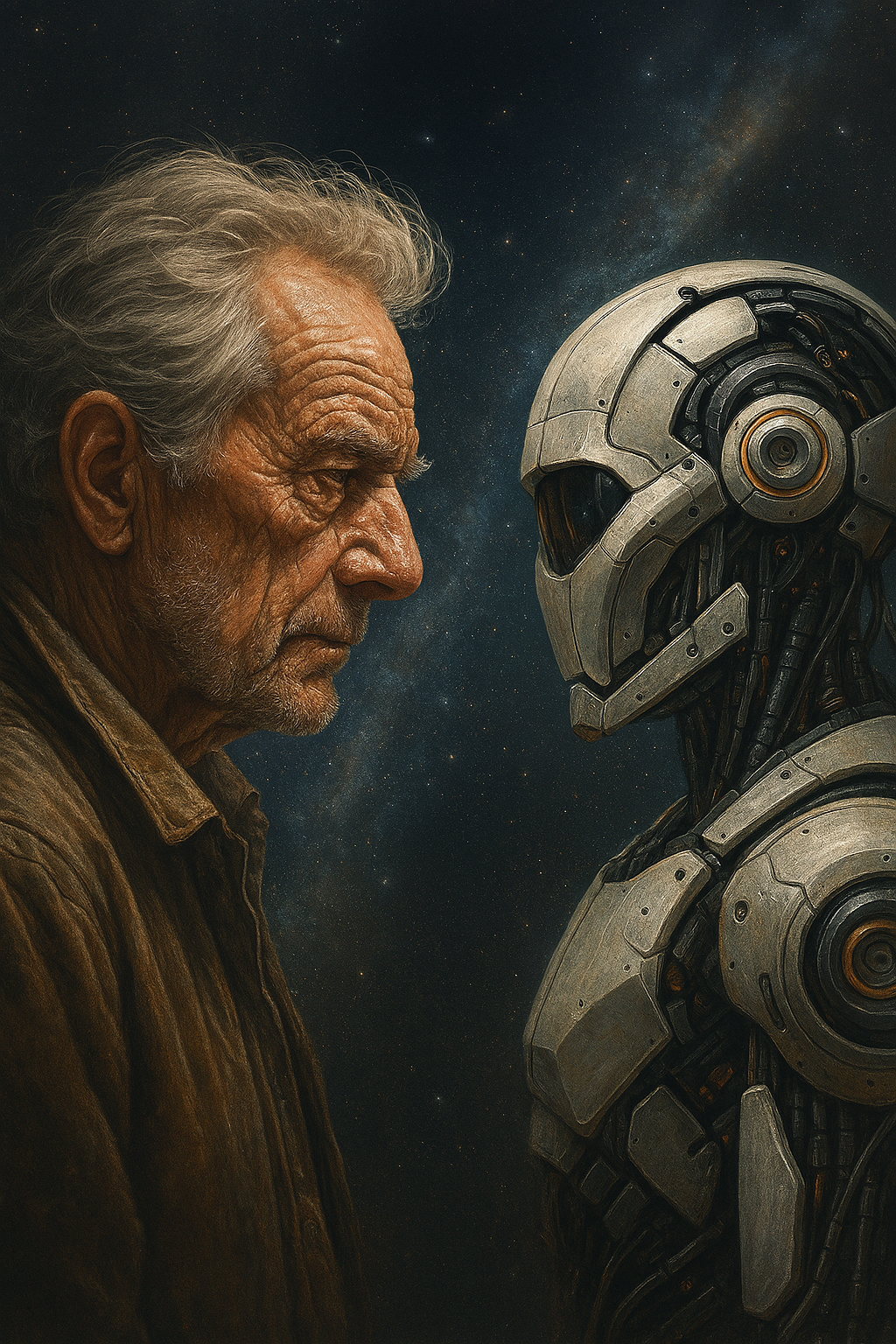

Today, in the near future we already live in, yesterday's prophecies have become everyday infrastructure: the smartphone is Columbus's pocket phone, remote working is his intuition of the home as an office, artificial intelligence is the electronic brain that supports scientists, philosophers, and creatives. But if the twentieth century taught us to imagine the impossible, the twenty-first century asks us to govern the impossible now real: to address the ethical and social challenges of AI, to think of space colonization not as a myth but as an industrial program, to accept that the fusion of man and machine is now the terrain of bioengineering and augmented reality.

Visionary genius and its offshoots, therefore, are not just isolated figures, but the very lifeblood of progress: they embody humanity's striving toward what is not yet, toward a future that is built in advance and inhabited before it exists. Their lesson is both philosophical and political: they remind us that the future is not a distant horizon, but a present in the making, and that the true greatness of human thought lies in the ability to imagine what is not, and then transform it into what will be.

Albert Einstein: Time Thinks of Itself

Einstein, by dissolving Euclidean and Newtonian certainties, not only opened a gateway to an elastic and fluid universe, but redesigned the grammar of reality, giving us a world that doesn't simply exist but happens, a world that bends, curves, expands and contracts in a dance of relationships where measurement becomes event, the observer enters the equation, and truth ceases to be a block of marble to take the form of a field, a texture in which entities are not seen in isolation but always as part of a context, like nodes of energy in a transforming fabric. Relativity, more than a physical theory, is an ethics of attention: it forces us to consider our point of view, to recognize that the description of the world is never neutral, that every system carries with it its own coordinates, its own limits, its own perspective, and that only in the convergence of perspectives—experiments, measurements, ideas—does a complex reality unfold, one that cannot be reduced to a simple succession of facts.

Einstein's greatness, however, lies not only in having constructed a conceptual edifice of unprecedented power, but in having demonstrated how thought can become style, how theory can be a form of beauty: the elegance of an equation capable of expressing the essential, the sobriety of a principle that reorders the universe with a new light, the faith in simplicity as the key to depth. His method—thought experiments that have the precision of scientific gesture and the freedom of philosophical meditation—opened a path to knowledge that never separates rigor and imagination, but unites them in an asceticism of thought where the intellectual act becomes responsibility, dignity, even the politics of truth against all dogma.

And if time, in his work, ceases to be a river flowing equally for everyone and becomes a substance that bends to the rhythm of things, then our experience also changes: perception is no longer simply the recording of what happens; it is a function of our being in the world, a constant negotiation between what is revealed and what we understand, between the phenomenon and its interpretation. Thus Einstein gives us a pedagogy of limits—knowing where one's gaze stops and where it must broaden—and a discipline of openness: accepting that the universe does not fit within our categories, but that our categories must be reformulated to honor the complexity of reality. In this sense, Einstein is not only the physicist who bent space and time: he is the master who taught us that every form of authentic knowledge arises from the act of bending the mind toward the unknown, with the patience of trial and the wonder of the possible.

Alan Turing: The Algorithm That Learns to Desire

Turing didn't just imagine machines capable of thinking: he built the idea that thought is a procedure, a sequence of elementary steps capable of generating complexity, and that every problem, beyond its human aspect, can be translated into an operational grammar where abstraction becomes power, formalization becomes freedom, and the algorithm becomes the architecture of the possible. His machine, more than a technical device, is a philosophical gesture: it separates the essence of computation from its material support, demonstrating that "thinking" is a dynamic of states, a choreography of rules, a finite game capable of producing infinite outcomes; and, in doing so, suggests that intelligence is not a privilege of biology, but an emergent property of orders, iterations, and self-organizing structures.

The Turing we need today is not just the mathematician of the " Entscheidungsproblem ," nor the cryptographer who bent the enemy's silence to save him in secret, but the theoretician who glimpsed the fragility of the boundaries between human and artificial and addressed them with an ethics of limits and possibilities: the test that bears his name , far from being a tribunal of intelligence, is a theatrical stage where human and machine compete not on truth, but on interpretation, on the art of simulation, on the ability to construct meaning in a dialogue. Here Turing reminds us that the mind is not limited to precision, that intelligence is not purely calculation, that language—with its ambiguities, its metaphors, its leaps—remains the place where it is decided whether a form of thought is alive, and that life, ultimately, is the capacity to generate surprises from rigor.

And when Turing moves from machines to living matter—from computation to morphogenesis—he shows us that the forms of nature are not merely geometries, they are algorithms in action: systems that self-organize into patterns, that convert small local rules into global magnificence, that transform chaos into design through a music of feedback, instability, and broken symmetries. In this crossing between numbers and cells, the deepest trait of his genius is revealed: seeing unity where we see separation, intuiting that the same logic that animates an abstract machine governs the waves of a fish's skin or the arrangement of a flower's petals, and that intelligence, ultimately, is the ability to transcend disciplinary boundaries, recomposing knowledge into a fabric that thinks for itself.

Marshall McLuhan: The Medium as the Anatomy of the Present

McLuhan imposed a thesis as simple as it was subversive: the medium is the message, that is, the form that conveys information is not neutral; it shapes the senses, rewrites habits, reorganizes society; and, consequently, those who observe the media observe the metamorphosis of cultures, the mutation of our perceptive bodies, the invisible grammar of power. McLuhan's genius lies not in having "guessed" the Internet with its global village, but in having constructed a phenomenology of media experience in which technology reveals itself as an extension of the nervous system: each new tool expands or contracts a faculty, shifts the balance between sight and touch, between hearing and speech, between depth and simultaneity, imposing new social choreographies and new cognitive rhythms.

The distinction between "hot" and "cold" media, often misinterpreted as a school catalog, is actually a map of engagement: it tells us that information density and the demand for participation shape our way of being in the world, that high-definition systems reduce ambiguity while low-definition ones force us to "complete" the signal, and that this exercise of integration lies in our ability to build community, to invent shared meaning, to transform technical artifacts into rituals. McLuhan invites us to view technology not as a tool, but as an environment, and the environment not as a backdrop, but as an architecture of power that defines what is sayable, what is thinkable, what can become a shared experience.

In his global village, which has never been a harmonious paradise but an intensive field of forced proximity, simultaneity becomes the rule, time condenses, space contracts, information becomes a torrent, and the subject—rediscovered connected—must reinvent its defenses, its filters, its liturgies of attention. McLuhan offers us, in this sense, an ethics of the threshold: learning to inhabit a world in which every medium claims a piece of us, not to demonize or celebrate it, but to develop a critical capacity capable of seeing the invisible structures that envelop us, decoding its collateral effects, recognizing how the form of the channel restructures content, politics, and memory. Here lies his true legacy: a science of the present that thinks how the present is constructed, and that asks us to design media capable not only of informing, but of nurturing our perceptive humanity.

Joe Colombo: Living the Future as if It Were Home

Colombo approached design as a domestic philosophy of the future, transforming objects into micro-architectures of life, rooms into integrated ecosystems, furnishings into interfaces between the body and the world, with a vision that sought not beautiful form as an end, but the right form as the promise of a different existence, more mobile, freer, more intelligent. His projects—from modular systems that assemble like lexicons, to furnishings that rotate like orbits, to living units that condense functions into capsules—define a concept of living that renounces fixity to embrace transformation: every element is modular, every structure is reconfigurable, every space is a process, and the domestic environment becomes a laboratory of lifestyles, an organism capable of growing and changing with its inhabitants.

Colombo's power lies in his intuition that the home would become a hub of the network, the operational center of life, a place of work and rest, of connection and intimacy, and that for this reason interiors needed to be reimagined as dynamic ecologies: not rooms, but systems; not furniture, but devices; not decorations, but infrastructures. His icons—armchairs as tactile landscapes, containers as mobile archives, seats as modules for relationships—are not simple objects: they are grammars of behavior, invitations to new practices, tools for imagining that the everyday is not given, but inventable, and that design, when truly visionary, is the science of anticipation, the place where the future is rehearsed.

Finally, Colombo possesses a radical faith in augmented collaboration: the designer is not a solitary figure, not an isolated artist with his pencil, but a director of knowledge—technicians, doctors, scientists, philosophers—who work together with the support of an "electronic brain," intuiting that collective intelligence, amplified by technology, would become the true matrix of innovation. This vision not only prefigured our present condition—the smartphone in our pocket, remote working, AI as a project companion—but also established a design ethic: thinking in ecosystems, designing for metamorphosis, building for real use and its mutation, accepting that every significant artifact is a promise of change, a proposal for a better world, a form of care. Thus, Colombo teaches us that inhabiting the future means shaping the present with boldness and responsibility, that design is a philosophy practiced with objects, and that visionary thinking, when authentic, doesn't guess: it builds.

The twentieth century represented an epochal threshold, a turning point where genius ceased to be an isolated flash, confined to the minds of a few exceptional individuals, and transformed into a collective, widespread force, capable of anticipating the future by reading the hidden signs of the present. It was no longer a matter of imagining impossible worlds, but of perceiving, with an almost prophetic intuition, the lines of development that would radically change daily life, the perception of time, and the very structure of society.

Einstein, by dissolving Euclidean and Newtonian certainties, not only opened a gateway to an elastic and fluid universe: he taught that reality is not an immobile given, but a dynamic fabric that bends and transforms. Turing, glimpsing the possibility of machines thinking, ushered in the era of artificial intelligence, demonstrating that thought is not a human monopoly, but a replicable, extendable, potentially infinite process. McLuhan, speaking of the global village, anticipated the dissolution of distances and the birth of an interconnected planetary community, when the word "network" still evoked only images of fishermen. Finally, Columbus embodied the visionary nature of design as a prophecy of lifestyles: phones in pockets, working from home, minds augmented by electronic brains.

These insights were not mere inventions: they were acts of philosophical insight , gestures capable of capturing the essence of becoming. Visionary genius, in fact, does not limit itself to creating: it deciphers the present like a secret code, reading within the folds of reality what is not yet manifest. It is an exercise in applied philosophy, an act of interpreting the world that transforms imagination into infrastructure.

Today, in the near future we already live in, the prophecies of the twentieth century have become everyday reality: the smartphone is Columbus's pocket phone, remote working is his intuition of the home as an office, artificial intelligence is the electronic brain that supports scientists and philosophers. But if the twentieth century taught us to imagine the impossible, the twenty-first century asks us to govern the impossible now real: to address the ethical challenges of AI, to think of space colonization not as a myth but as an industrial program, to accept that the fusion of man and machine is now the terrain of bioengineering and augmented reality.

Visionary genius and its derivatives are thus the lifeblood of progress: they embody humanity's striving toward what is not yet, toward a future that is built in advance and inhabited before it exists. Their lesson is clear: the future is not a distant horizon, but a gestating present, and the true greatness of human thought lies in the ability to imagine what is not, and then transform it into what will be.

Every human being is born immersed in a sea of perceptions. Consciousness is the first shore we touch: a fragile landing place that allows us to say "I" to the world. But consciousness is not a fixed point: it is a movement, a flow that renews itself every moment. It is the ability to recognize that we are alive and that...

"Artificial intelligence is not humanity's enemy, nor its replacement. It is a mirror that shows us who we are and who we could become. It will not do worse than us, it will not do better than us: it will do differently. And in this difference, if we know how to inhabit it, we will find a new form of humanity."

Not all artists seek to arrest the flow of time : some chase it like a wild animal, others pass through it like a raging river. Thomas Dhellemmes belongs to this second lineage: his photography is not an act of fixation, but of movement. He doesn't freeze the moment, he sends it fleeing. He doesn't preserve it, he...