The Forest of Correspondences: A Philosophical Warning for Our Time

Charles Baudelaire , in his famous sonnet Correspondences , gives us a vision that is not only poetic, but prophetic. Nature, he says, is a temple: a sacred place where every element—scents, colors, sounds—is intertwined in a secret language, a song that speaks to man and invites him to recognize his belonging to a larger order. " Nature is a temple in which living columns sometimes let out confused words; man passes through it, through forests of symbols, which look at him with familiar gazes. Like long echoes, which from afar merge into a dark and profound unity—vast as the night and the light—the scents, colors, and sounds respond to one another. Scents fresh as the flesh of children, sweet as the sound of the oboe, green as prairies. And others corrupt, rich and triumphant, vast as infinite things: amber, musk, benzoin, and incense, which sing of the raptures of the spirit and the senses ."

Synesthesia as a revelation

Baudelaire 's images are not mere literary ornaments: they are instruments of revelation. Synesthesia—the scent that becomes sound, the color that becomes emotion—reminds us that reality is not fragmented, but woven of correspondences. Every perception is a bridge to unity. In this interweaving, man is not a spectator, but an integral part: he passes through the forest of symbols and is observed, recognized, and called upon.

The hidden warning

If nature is a temple, then any act that harms it is a sacrilege. Baudelaire invites us to understand that our relationship with the world is not utilitarian, but sacred. We are not masters of the forest, but pilgrims who enter it with respect. His message, read today, becomes a warning: changing things while there is still time means recognizing that the destruction of nature is the destruction of ourselves, because connections are not broken without consequences.

Sensory experience as a path to consciousness

Entering the forest means engaging with all five senses. The sight of mysterious wonder, the scent that evokes memories and presences, the sound that becomes a melodious song: everything invites us to wonder. Wonder is the first form of consciousness, the sign that we are alive and capable of recognizing beauty. Without wonder, life becomes a mechanism; with wonder, it becomes revelation.

An invitation to transformation

Baudelaire 's message is not nostalgia, but a call to transformation. The infinite correspondences between us and nature remind us that every action has an echo. If we choose to live with respect, gratitude, and attentiveness, then nature's song will continue to respond to us. If, however, we choose indifference, the silence that follows will be a sign of our own loss.

Philosophy as responsibility

A philosophical direction that arises from these words is clear: philosophy is not just speculation, but responsibility. It is the ability to read symbols, to listen to secret voices, to recognize that life is a web of correspondences. Changing things means returning to living with awareness, with wonder, with respect.

Baudelaire offers us a warning that today resonates more urgently than ever: nature is a temple, and we are called to protect it. It's not about ecology as a technique, but about philosophy as an ethic: recognizing that beauty, dignity, and life itself depend on our ability to hear the secret song of the forest.

Let this warning become your guide: do not wait for silence, but respond now, while the song still envelops us.

ABOUT...

Foolishness, error, sin, and avarice inhabit our spirits and agitate our bodies; we nourish sweet remorse as beggars nourish their insects.

Our sins are stubborn, our repentances cowardly; we make ourselves pay handsomely for our confessions and joyfully return to the muddy path, convinced that we have washed away all our stains with miserable tears.

It is Satan Trismegistus who lulls our bewitched spirits on the pillow of evil, evaporating, like a learned chemist, the rich metal of our will.

The Devil holds the strings that move us! Repugnant objects fascinate us; every day we descend a step toward Hell, without feeling horror, passing through mephitic darkness.

Like a depraved villain kissing and sucking the tortured breast of an ancient whore, we steal a clandestine pleasure on the fly and squeeze it forcefully, as if it were an old orange.

Crammed together, swarming like a million worms, a population of demons revels in our brains, and when we breathe, death flows into our lungs like an invisible river with dark groans.

If rape, poison, the dagger, the fire have not yet embroidered with their pleasing forms the banal canvas of our miserable destinies, it is because we lack, alas, a sufficiently bold soul.

But among the jackals, panthers, bitches, monkeys, scorpions, vultures, snakes, among the monsters that yelp, howl, and grunt within the infamous menagerie of our vices, there is one more foul, more evil, more filthy. Though he makes no grand gestures or utters shrill cries, he would gladly reduce the earth to ruins and swallow the world in a single yawn.

It is Boredom! His eye, burdened by an involuntary tear, dreams of scaffolds while smoking his pipe. You know him, reader, this delicate monster—you, hypocritical reader—my fellow man and brother!

One of the most powerful and disturbing pieces of Les Fleurs du Mal.

Baudelaire doesn't just describe human vices and failings: he stages them like a menagerie of wild beasts, an infernal theater where every sin is a demon living within. But the real stroke of genius comes at the end: of all monsters, the most terrible is not violence, nor lust, nor avarice. It is Boredom.

Baudelaire's diagnosis

Foolishness and sin: these are not exceptions, but daily habits. Man deludes himself into believing he can purify himself with superficial repentance, yet he continues to tread the "muddy path."

The Devil as puppeteer: the image of "Satan Trismegistus" who evaporates the will is a metaphor for our inability to resist degrading attractions.

The menagerie of vices: ferocious and repugnant animals represent the variety of passions that devour us. Yet, above all this, Baudelaire places Boredom: a silent, unassuming monster that consumes life from within.

Boredom as a radical evil

Boredom is not simply a lack of enjoyment. It is the void that opens when man loses meaning, when he can no longer marvel or create. It is the evil that would reduce the earth to ruin "in a single yawn." Baudelaire describes it as a delicate yet devastating monster: a subtle poison that corrodes the will and transforms existence into a slow spiritual suicide.

The warning for our time

Today, more than ever, this text resonates as a warning. We live surrounded by stimuli, but often devoid of meaning. Boredom disguises itself as saturation, routine, compulsive consumption. It is the risk of living without depth, of reducing life to a repetitive mechanism.

Baudelaire invites us to recognize that the real danger is not only visible sin, but the indifference that anesthetizes us. Boredom is the death of the soul even before the body.

Philosophy as an antidote

The task of philosophy, then, is to break this spell. Not with superficial distractions, but with the search for meaning, with wonder, with the ability to see connections where there seems to be only emptiness. Philosophy becomes an act of resistance: a way to avoid being swallowed up by the silent monster.

Baudelaire gives us an image that is both poetry and prophecy: Boredom as a monster devouring the world. His warning is clear: it's not enough to avoid sin, we must avoid indifference. It's not enough to live, we must live with intensity, with awareness, with wonder.

Every human being is born immersed in a sea of perceptions. Consciousness is the first shore we touch: a fragile landing place that allows us to say "I" to the world. But consciousness is not a fixed point: it is a movement, a flow that renews itself every moment. It is the ability to recognize that we are alive and that...

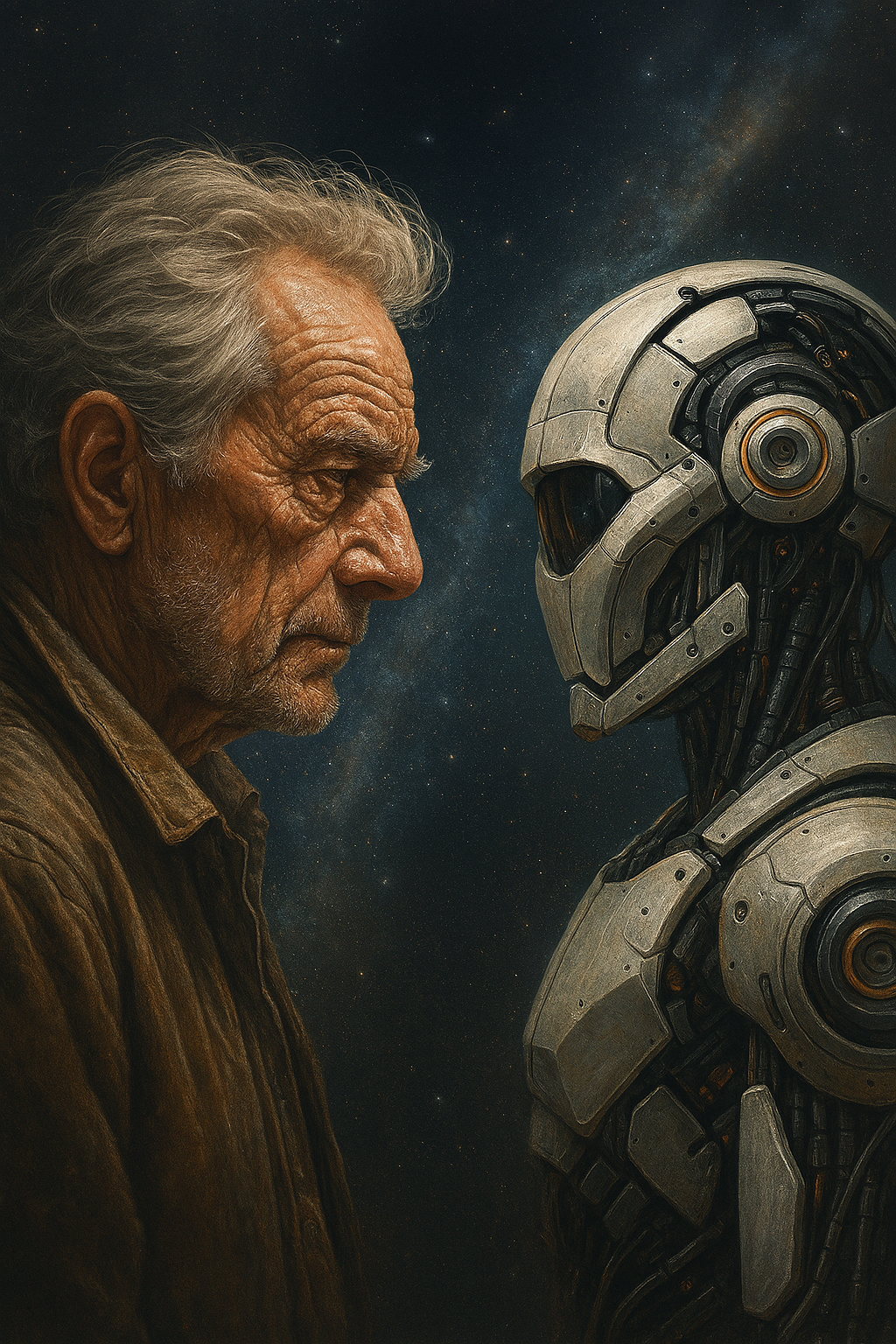

"Artificial intelligence is not humanity's enemy, nor its replacement. It is a mirror that shows us who we are and who we could become. It will not do worse than us, it will not do better than us: it will do differently. And in this difference, if we know how to inhabit it, we will find a new form of humanity."

Not all artists seek to arrest the flow of time : some chase it like a wild animal, others pass through it like a raging river. Thomas Dhellemmes belongs to this second lineage: his photography is not an act of fixation, but of movement. He doesn't freeze the moment, he sends it fleeing. He doesn't preserve it, he...